Here's another easy win—never make users log in to unsubscribe from email notifications. For nearly every website, there's no security risk in allowing users to unsubscribe without logging in, and there are many benefits, including goodwill from users and fewer spam reports. Unfortunately, most popular sites don't take the simplest approach to solving this problem.

Bad approach: Twitter & Facebook

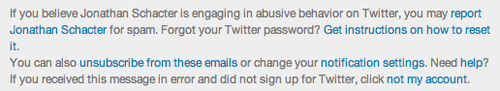

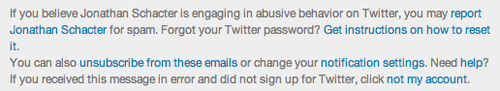

Twitter sends a lot of different kinds of notifications, and their approach to notification management is complex—as evidenced by their incredibly complex footer text, which wouldn't fit into 2 tweets, let alone one.

When you get a specific kind of notification (e.g. "@dzohrob is now following you on Twitter!"), you can disable *only* that notification type with one click. However, any other action requires you to log in, which means trying to remember your password and potentially going through a reset password process.

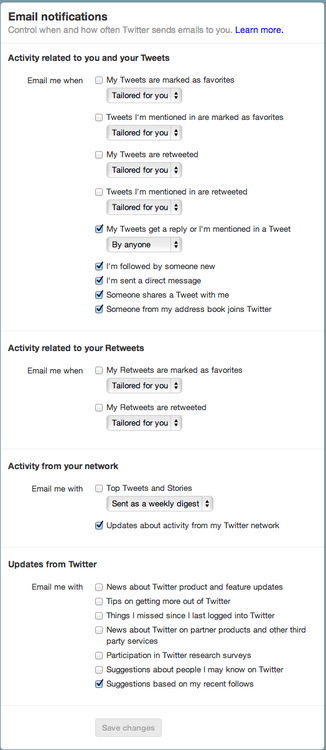

Let's say you remember your password—now you're presented with a list of 21 different notification types, some of which have sub-options. And of course, there's no way to unsubscribe from all of them. What an awful user experience.

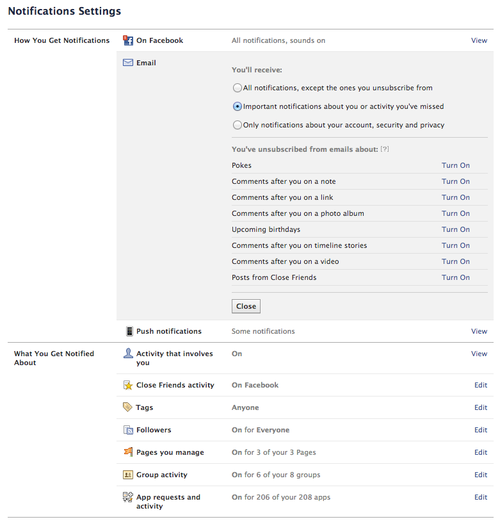

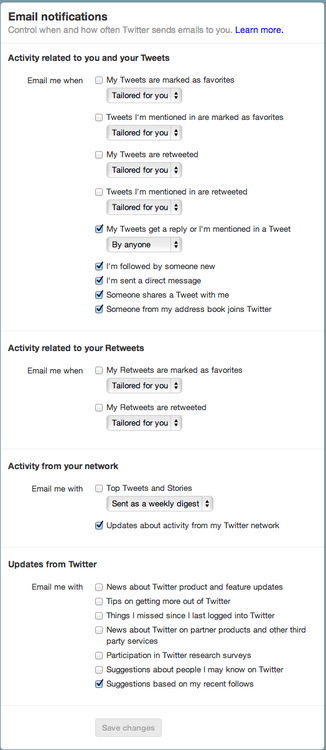

Facebook takes a similar approach, allowing you to opt-out of one notification type, but requiring a login for any other management. Their notification management page is slightly better than Twitter's, but there's still no way to unsubscribe from all notifications with one click.

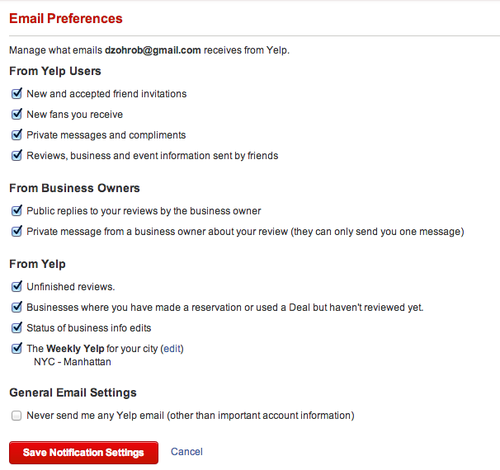

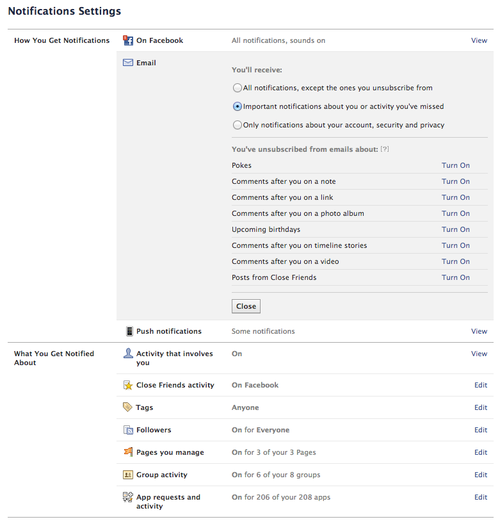

Good approach: Yelp

Yelp does it right. Even though they send many different types of notifications, like Facebook and Twitter, their unsubscribe link lets me manage the email I receive from them, and even lets me unsubscribe from all emails with one click. Nice work.

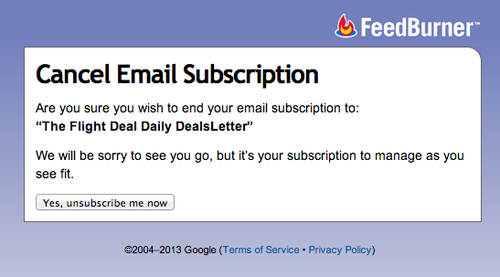

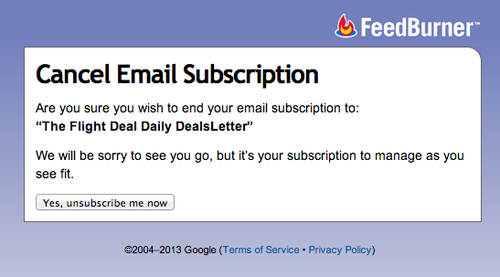

Bad approach: Feedburner

I'm not sure what kind of problem the "unsubscribe confirmation" page actually solves. Accidental clicks on unsubscribe links? Forwarded emails? Either way, it makes users do extra work for little benefit. I hope this pattern disappears over time.

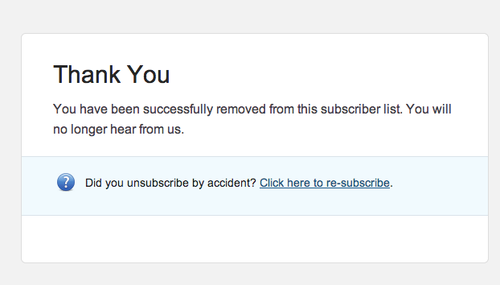

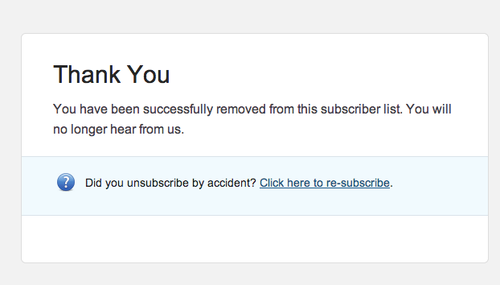

Good approach: Campaign Monitor & MailChimp

Thankfully, companies like MailChimp that specialize in email delivery offer much better subscription management links. For example, I just got an email from SXSW—clicking through results in an instant unsubscribe, with the option to resubscribe.

Doing it the right way is easy

It's easy to choose a UI pattern for your unsubscribe links.

If your service sends many different types of email, follow Yelp's lead -- let users click through and manage all notification types without logging in. If you're sending a newsletter, let them unsubscribe with one click.

Make the right choice. You'll make your users happier and reduce your spam reports.