I’ll admit it—I love programming, and I have since I was a kid. This makes me a nerd, but at least I’m an honest nerd.

Code is a unique medium. There’s no activity better suited for the achievement of flow, which Wikipedia defines as “the mental state of operation in which a person in an activity is fully immersed in a feeling of energized focus, full involvement, and success in the process of the activity.”

There’s something really special about hacking away on something and then, after hours or days of struggle—making it actually work. And that joy of completion, of having heroically struggled and then solved the problem, happens again and again. A good programmer working on a hard problem has little dopamine bursts firing in their brain all day.

I’m still not over it. And I think many people would benefit from (and enjoy!) learning how to code.

A computer on every desk, and in every home

Steve Jobs gets most of the credit for being a revolutionary technology leader, but Bill Gates was equally, if not more, visionary. In 1980, Gates defined the mission of Microsoft “A computer on every desk, and in every home.”1 It’s difficult, now that we we all have incredibly powerful computers in our homes, cars, and pockets, to remember how insane this was at the time.

Microsoft executed that insane vision nearly flawlessly.

Computers became integral to many jobs in the 1980s and especially the 1990s, as the Internet penetrated workplaces and Microsoft’s Office software became ubiquitous. New software dramatically changed the nature of office work.

We’re about to experience another dramatic change. The New York Times recently published The Age of Big Data. You should read it, but let me summarize: As computers become part of more things (phones, cars, toasters), they will generate more and more data, and we’ll need smart analysts to make sense of it all. Office workers will experience a big shift like they did in the 90’s,as the ability to analyze data becomes more integral to every job—from management, to marketing, to design, to front-line information workers.

I believe that simple computer proficiency will no longer suffice as software takes over more aspects of work and life. Not that it’ll be necessary for all office workers to become masterful programmers; but those who can write simple programs to help automate their daily work and make sense of piles of data will have an advantage.

This change means more people will have the opportunity to experience the joy of code. Unfortunately, learning requires hard work, and most people haven’t been educated in the basics of computational thinking.

How will all these people learn how to code?

Learn BASIC now

When I was around eight years old I asked my parents to buy me a book called Learn BASIC Now. (Amazingly enough, Amazon still sells the book for a penny.) I remember sitting down at the computer in our living room and working through the book’s exercises in QuickBASIC, a programming language included with most PCs at the time.

Within a few weeks I was able to make simple video games, and by the time I was in middle school I was asking my parents for related stuff—more books, then an Internet connection, then a domain name (which cost $100 at the time!) and Web hosting service, so I could help others learn.2

One of the most popular games I wrote as a kid had primitive graphics that looked like this:

This wasn’t state-of-the-art for 1994, but it was playable and maybe even fun. I called the game Lander. The goal was to safely pilot your ship to a landing strip on the moon, avoiding obstacles along the way3. I really enjoyed making games and sharing them with friends and on the Web—it was a great motivator for me to improve as a programmer.

But what worked for me wouldn’t work today. The everyday systems we use have become more complicated, and it’s harder to create a simple program of acceptable quality.

Most DOS users would be able to find and run GW-BASIC or QuickBASIC, two programming languages that shipped with the operating system—but although current Macs ship with several powerful languages installed, most newcomers wouldn’t know where to find them. If they could, the Terminal would seem scary because the Mac user interface covers up its text-based underpinnings.

Even then, creating a text-based program wouldn’t seem that impressive—the simplest iPhone apps come with beautiful, animated interfaces that react instantly to our touch, courtesy of Apple’s design tools. A text-only number guessing game seems pretty lame by comparison.

Learning to code in 2012

So how does one get started, given the complexity of today’s computers and the high expectations of users? Thankfully, many startups and universities have begun tackling the problem in innovative ways.

Udemy offers a class by Zed Shaw called Learn Python the Hard Way for $29. Zed also offers a free HTML book for the course. Zed’s premise is that the best way to learn is by doing, so you’ll be doing a lot of typing. This seems to me like a Good Thing.

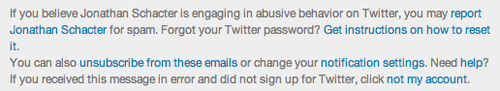

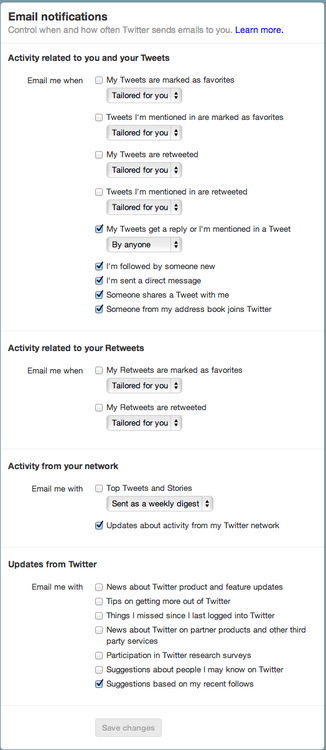

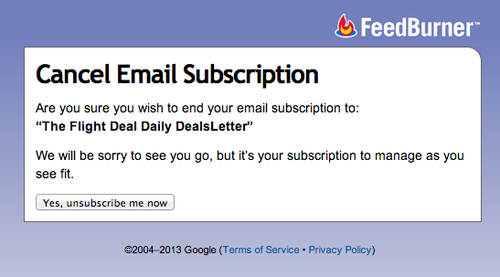

Another startup called Codecademy offers a unique way to learn—simple, step-by-step tutorials that run in your web browser, allowing you to interactively learn how to code without installing any software or buying any books. They’ve recently received a lot of press for a 52-week program called Code Year. When you sign up for Code Year, you receive a weekly code lesson via email which you can complete on their website. There are also Q&A forums where you can get help with each lesson. Hundreds of thousands of people have signed up, including high-profile folks like Mike Bloomberg.

There are a couple of potential downsides to Code Year and Codecademy. Currently, they only teach Javascript, which I wouldn’t recommend as a first language for a beginning programmer. Second, the interactivity of the lessons hides some of the realities of coding. Programming is a unique activity because for the most part it’s a very solitary journey—you’re alone with your work, shuffling logic around your brain. I’m curious if the folks who go through Codecademy tutorials are ready for the kinds of frustrations they’ll face—Learn Python The Hard Way is much more like “actual” programming.

There are tons of other great resources, far too many to list here. The Khan Academy has great video lectures; Google offers excellent Python tutorials; MIT offers their Intro to Computer Science and Programming, and Stanford offers an Intro to Computer Science and Programming Methodology..

Regardless of which method you end up trying, if you want to learn, find something that appeals to you and stick with it. Don’t get discouraged; the rewards will reveal themselves over time.

Conclusion

Learning to code is like learning to play an instrument. Some people will achieve basic easier than others. But for nearly everyone, becoming a good programmer will take many hours of deliberate practice; it’s not something you can achieve in hours or days, no matter how many tutorials you read.

To be a great programmer, you have to really want to learn; it’s not going to happen in a day or a week. Thankfully, you probably don’t need to become a great programmer unless you plan to pursue a career in software engineering. You can learn enough code in a short time to improve and automate some of your daily work.

I hope that the changes ahead as we enter the “Age of Big Data” give more people the opportunity to experience the joy of code.

I’d love to hear from people who want to learn code. If you find a particular resource linked in this post helpful (or terrible), or you think I’ve missed something, please let me know.

Notes

1 The full quote is actually “A computer on every desk and in every home, all running Microsoft software.” Steve Jobs deserves praise for rescuing Apple in the early 2000s and taking leadership of the technology industry, but it was Microsoft who really brought personal computers to the masses.

2 Sure enough, some of my tutorials are still floating around the Web. This taught me an early lesson in how anything you put on the Internet never goes away.

3 The game borrowed from similar “land the ship” games at the time. A bit more explanation on its mechanics: the turquoise strip at the bottom of the screen represents a lunar landscape; the red flaming comet is an obstacle to avoid; and the shaded golf ball-like things are supposed to be planets to dodge. (Don’t ask me why planets are hovering above the moon’s surface; it made sense at the time). The code for this game still floats around the internet—it’s embarrassing.